Adaptation does not happen in a vacuum. It needs specific knowledge and skills to be made available to the many. We can only harness the energy and ideas of society through education, and adaptation works best if the solutions are designed as close as possible to where the impacts are being felt.

We are referring to education across the different stages of life, from schooling to universities and technical education as well as through adult learning and training in all its forms. If we take this broader view, universities, national think tanks, research entities, and local learning institutions are all part of the broad mix of institutional stakeholders necessary to transform education systems.

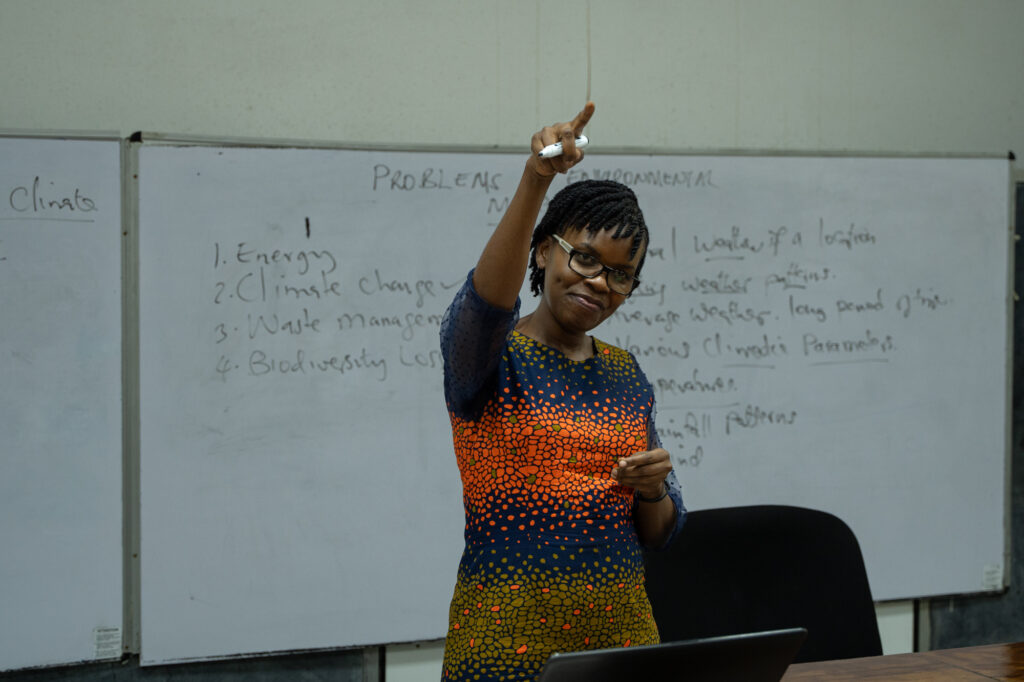

Student in Kenya. Photo credit: Lorenzo Franchi 7 UN CC:Learn

Here are three reasons why we think that climate change education deserves a closer look.

1- Countries are asking for help. Many countries have a keen interest in refocusing their education systems towards climate change action. This is because they realise that both current and future generations need to have a deeper understanding of the issues at stake when it comes to climate change. You only have to look as far as the NDC Partnership’s national frameworks to see this demand coming through almost universally.

Development partners, perhaps led by the UN system, need to do more in this space. Systematic (rather than piecemeal) assessments of needs can bring greater visibility and engagement. The One UN Climate Change Learning Partnership (UNCC:Learn) has been developing national learning strategies for a decade offering a wealth of experience covering formal, informal, and non-formal education measures. Learning action plans covering all NDC sectors and supporting general education provide a further step.

Investment plans to support these proposals would take us one step further, as we are seeing in countries like Namibia, Bhutan, and Zambia: Namibia has linked accessing USD 18 billion in climate finance for its NDC to ensuring ‘retention of nationals with the necessary skills and knowledge’; Bhutan has made its national educational institutions a central pillar of its National Adaptation Plan, to train public sector officials in adaptation and resilience on a recurrent basis; and Zambia is launching a major climate change education project that seeks to transform its education system as a driver for green growth. These are important steps that are being taken by countries to consolidate gains made on adaptation towards a green and fair economic transition.

2- Climate education pays off. The Global Center on Adaptation documents several case studies on the relationship between climate change, vulnerability, and education. As its 2022 Report on “State and Trends in Adaptation” says:

‘Africa has a large and growing young population, with about 60 percent under the age of 25. While the sheer size of this young population poses challenges in terms of providing education and employment, it also brings major opportunities …. in ways that can accelerate economic growth, build resilience, and drive transformational adaptation.’

Classroom in Mauritius. Photo credit: Lorenzo Franch / UN CC:Learn

The UN CC:Learn experience on financing climate education is also quite telling. Small investments in planning for climate education can unlock much larger financing. For example, the Dominican Republic was one of the first countries to receive a UN CC:Learn grant back in 2012 which it used to leverage millions of dollars of public money to train primary school teachers across the country. More recently Zambia has been successful in leveraging a major IKI grant (17 million Euro) for climate education based on a UN CC:Learn grant of $100,000 in 2018.

3- Long-term solutions to the climate emergency must engage those on the frontlines. We are talking about interventions that go beyond ‘consultation’ and that involve local communities as the principal architects of adaptation action. Despite well-intentioned efforts to consult more effectively in project design, many development practitioners would probably agree that those principal architects often sit many hundreds or even thousands of miles from where the impacts are being felt. And indeed there are multiple reasons for this; some having to do with global financing structures.

Turning this tendency around will require an approach that invests in education, research, and learning through partnerships with universities and other training and research institutions. Such an approach would help to unlock national potential, strengthen locally driven research, engage with indigenous solutions, and better document what works and why.

The Organic Farm7 is an organic farm in Zambia that uses innovative irrigation techniques to water crops and solar energy as its primary energy source. Its founder, Mr. Abel Hangoma, an engineer by profession, is committed to teaching his methods to other farmers. Photo Credit: Lorenzo Franchi / UN CC:Learn

UNDP is a member of the Adaptation Research Alliance – a global coalition on action-oriented research that informs adaptation solutions. The work of the ARA emphasises learning as a driver of solutions, particularly at the local level. This work builds on UNDP’s long-standing support to countries to strengthen knowledge and skills both at the community level and within different tiers of government.

Learning and education take place throughout a lifetime, both in and out of school. It may occur in the community, in more distant locations, and increasingly online. At the global level, the Massive Online courses developed by UNITAR and UNDP have reached tens of thousands of practitioners.

Below are some resources from the UN CC:Learn platform, which covers nearly 100 courses in multiple languages and trains more than 100,000 individuals per year.

- National Adaptation Plans: Building Climate Resilience in Agriculture (UNITAR/FAO/UNDP partnership)

- Building Climate Resilience through Ecosystem-based Adaptation Planning (UNITAR, UNEP and UNDP partnership)

Is it time for a fresh look at climate change education? We think so.